1 September – I’ll be one day and a bit, in Winnipeg. On the land, and on the water too.

The theme of land and rivers, the two great pathways of our country, keeps gaining strength. Not because I intellectually seek it out. Because it is imposing itself on me.

A tear-off map at my hotel inspires my walk: down to the Red River, there behind the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, and then along the walking trails up into Stephen Juba Park, back down and around the curve of The Forks (where the Assiniboine River joins the Red), onto the water in a 30-minute tour, and more river-side walking, both rivers.

The Red River. The cereal of my childhood, even my very own Red River coat, as a child.

The river, of course, is more important for reasons other than cereal and coats.

My path along the Red up into Stephen Juba Park leads me past old pilings, last remnants of the glory days of this port (before the Panama Canal opened, and offered shipping an easier, quicker route through the Americas).

This is also when I first tap my boots in the water.

Literal next step in a whimsical project I hope I can complete: having tapped toes in the Pacific (Burrard Inlet, cf. my post of 25 August), I want now to tap them in the Red River, Hudson Bay and Lake Ontario.

Did you notice the trestle bridge, in the distance of that last photo? Used for military purposes, I’m told, and now the train bridge. I’m drawn to it. I admire the utility of these bridges, their visible geometry and, once I draw near, the majesty (albeit scruffy) of the near end of this particular example.

After I turn, after I follow the riverwalk bend around the point of land, I am now beside the Assiniboine River. I tap toes in its waters as well — a bonus not part of the original plan — and, as I do so, I notice a yellow Waterways tour boat mid-stream.

There is a dock, there is a boat about to depart, I climb aboard.

Only one fellow passenger, this early in the day: a Montreal film-maker, in town to work on a production here. Our guide has an impeccably Spanish name and an impeccably Canadian accent: his family moved here when he was two years old.

Kayak going one way, we’re going the other. Miguel is powering ahead, having now explained those three lines on the bridge pillar. Each is a water level: blue for normal spring levels, yellow for the danger of rising waters, red for floods. (I think of my brother’s years in Winnipeg, and the spring he helped sandbag against that year’s inundation.)

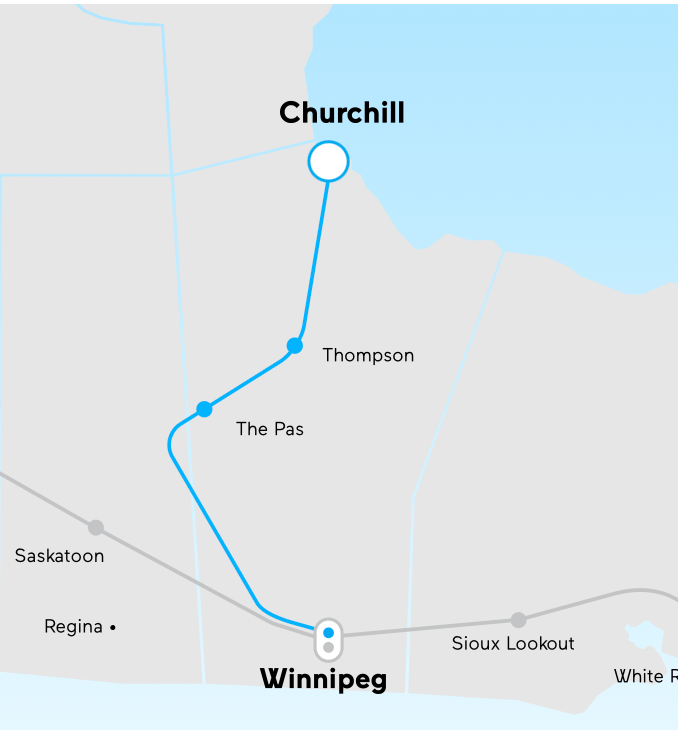

Back on land, toes duly tapped in not one but two mighty rivers, I head for the markets within The Forks complex. While you can buy food aboard the Winnipeg-Churchill run, it’s the like of microwaved subs, I’ve been told — the same person then suggesting I lay in some supplies.

So I do. Bison Snack Sticks (Canadian), Thunderbird “real food” bars (American), oat cakes (Isle of Mull) and Gemini apples (very very very local). Tomorrow morning, I’ll snag myself a few hard-boiled eggs from the hotel’s breakfast bar as well.

Feeling sufficiently prepared, I leave The Forks. But not before I admire Caboose 76602, a permanent installation on the grounds.

Built in Montreal in the 1930s, retired from service in Winnipeg in 1988, it is now “dedicated to the thousands of CN train crews who travelled through Winnipeg and the ‘East Yard’ that is now The Forks.”

Tomorrow, 12:05 pm Central time, I’ll be back on board one of today’s trains.

The one that will take me to Churchill.